- Home

- Alison Lloyd

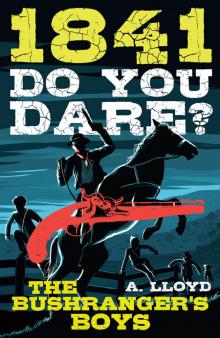

Do You Dare? Bushranger's Boys

Do You Dare? Bushranger's Boys Read online

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

1

Jem gripped the money tight. He felt the hard edges of the silver coins in his palm. He waited with his dad. Their sheepdog, the Old Girl – lay warm across his feet. She chewed a piece of bark that had fallen from the roof.

Jem had always lived in this slab hut. His dad had built it, but it wasn’t theirs. It belonged to Captain Ross. So did the sheep and the four miles of land in front of them. So did another run and the Station, twenty miles away. But today could change all that.

The money Jem held, knotted in a handkerchief, was their own. It had been saved penny by penny, year by year. Jem had gone without shoes to make up the last few shillings. That’s why Jem’s dad let him hold it. Ten whole pounds, it was. The price the Captain wanted for this run. Today the Captain was coming to get it. He had promised to sell them the land.

The Old Girl stopped chewing and began to growl. A minute later, Jem saw the Captain riding up the paddock. He had a quality horse. She had a white diamond on her face, a shiny coat and fast legs. For some reason, the Captain was also leading an old mare with a hide like a scrubbing brush. She wouldn’t be a gift, that was for sure. Not from the Captain.

The Old Girl’s hackles rose. Her ears flattened against her skull. She stood up and approached the Captain’s horse warily, with a deep growling bark.

‘Hush now,’ said Jem’s dad. He took off his hat and rubbed the brim with his thumb. He was afraid of the Captain too, Jem thought.

‘Call off your damn dog,’ Captain Ross ordered.

Jem’s dad whistled. The Old Girl backed up a few steps.

Captain Ross stayed on his horse. ‘So you still want to buy this run?’ he said.

Jem’s dad nodded.

Captain Ross looked out over the paddocks. ‘I’ve reconsidered,’ he said.

Jem’s dad turned his hat around and around. He looked at the Captain.

‘I’ll offer you a fair deal,’ the Captain said. ‘Thirty pounds – and you can keep half the sheep.’

Thirty pounds! Jem’s dad didn’t have thirty pounds – would never have thirty pounds. He already worked until he was too knackered to eat. Captain Ross knew that, of course. That would be why he’d put the price up. Jem wanted to throw the bag of money in his face and smack his stuck-up nose.

Another growl rumbled in the Old Girl’s throat.

Jem’s dad gripped his hat like he was holding it together. ‘I’ve been an honest worker for you all this while,’ he said. ‘You can’t take less?’

Captain Ross twitched his black moustache. ‘In my book,’ he said, ‘once a thief, always a thief. You might be free, but you’ve done no more than make up what you owe.’

What about the money we saved? Jem wanted to say. But he saw the Captain’s hand curl in a fist around the gun strapped to the front of his saddle. It was an expensive musket, with swirls of brass in the stock. It was as if the Captain was saying: do you really want to argue with a man like me?

Captain Ross shrugged his shoulders. ‘I will make you an offer,’ he said. ‘I need more men at the homestead, now that I can’t get new convicts. Your son is tall for his age. I’ll employ him on half wages.’

Jem’s dad put a hand on his son’s shoulder. ‘Jem’s a good boy,’ he said. ‘He’s good with animals. I was planning to keep him with me.’

‘These are my animals, and I don’t need him here,’ said the Captain. ‘He can work in my stables.’

Jem’s dad rubbed his hand slowly over his face. It gave Jem a bad feeling in his guts – his dad usually did that when a lamb wasn’t going to make it. His dad bent down and undid his boot laces. Jem saw the old red scars that ringed his father’s ankles, from the convict shackles Captain Ross had once locked him in.

‘Dad?’ Was his dad agreeing? Did this mean Jem was leaving?

Jem’s dad took off his boots and gave them to Jem. ‘Better wear these, son. You don’t want the Captain’s horses busting your feet.’ He took the handkerchief with the money.

Jem put on the boots. They didn’t fit right. The whole day didn’t fit right. Jem didn’t want to go anywhere.

Jem’s dad put his hand on his son’s back, and pushed him gently towards the Captain. Jem clomped forward awkwardly. He climbed onto the old mare.

The Old Girl watched with her head on one side like she couldn’t work it out. Jem would have liked to kiss her goodbye, but not in front of the Captain.

Captain Ross spoke to Jem. His long black sideburns underlined his jaw. ‘You’d better not follow your father’s bad ways,’ he warned, ‘or you’ll come to nothing. I’ll make sure of it.’

Jem was silent, because he felt like nothing he said would make any difference. He felt as if his life had been taken off him and stuffed inside the Captain’s saddlebags.

The Captain flicked his riding whip, the diamond-faced filly flicked her hooves, and the mare shambled down the track after them, carrying Jem away.

Jem saw the Old Girl look from him to his dad. She began to bark. When Jem reached the rise, the last place he could see home from, she broke away. She pelted across the paddock to Jem. The Captain’s horse skipped sideways and nearly threw him. The Captain cursed.

‘Go home, Girl,’ Jem told her.

But she wouldn’t. She came at the horses, barking. She was trying to round him up, Jem knew, as if he was a stray sheep that should return to his pen.

Before Jem realised, the Captain had taken his musket from the saddle. He cocked the trigger, and lifted the weapon to his shoulder.

‘No!’ Jem shouted.

Captain Ross didn’t listen. His finger moved on the trigger. Smoke and noise exploded around them. Both the horses jumped. Jem didn’t try to stay on. He hit the ground hard, stumbled to his feet and ran to the Old Girl.

She was lying on her side when Jem got to her. He saw a long shiver go through her body, head to tail. Her four paws quivered. Then they stopped.

Slowly, Jem turned to face the Captain. Jem was shaking.

‘I hate you,’ he said.

‘Why should I care?’ Captain Ross replied. ‘Get back on that horse.’

Jem sat like a lump of wood while the horses plodded on. He kept imagining the Old Girl was following them.

When the horses stopped, Jem noticed they had reached the place where the wattles closed in along the river. He had heard of a stickup here by a bushranger, not long before. He saw the Captain’s fingers hook over his musket barrel again. Jem tensed.

The Captain looked up and down the river. He turned and spoke to Jem. ‘When we’re over the creek, we’re back on my land,’ he said.

His land, thought Jem. Such a lot of land. How did he come to have all that, and Jem have nothing? Not even a dog.

The horses tilted down the bank, their hooves slipping on the icy mud. The Captain’s horse surged into the river. Jem’s horse stopped dead in the mud. Jem gave her a prod in the flanks. But she wouldn’t budge. She shook her head as if she didn’t like walking all this way with a strange boy on top. Jem didn’t like it either.

The Captain stopped on the far side and looked back again.

‘Daisy!’ he said sharply. ‘Move.’

That was when Jem saw the man up ahead. He wasn’t hiding in the bushes. He was leaning against a gum

tree. He waved at Jem. But it wasn’t a ‘g’day’ wave. More of a ‘stay back’.

What’s more, he had a red scarf tied over his face. In his right hand was a slim dark shape – a pistol. It was the bushranger.

The man was signalling him to dismount, Jem realised. He slithered to the ground.

Captain Ross still had his back to the path ahead. He raised his voice at Jem. ‘What the deuce! Get back on the horse, boy.’

Jem didn’t. He stood perfectly still.

The bushranger nodded at Jem. He lowered his pistol so it was pointing at Captain Ross.

‘Sir!’ he called.

Captain Ross turned around. Jem couldn’t see the Captain’s face, but he saw his back and shoulders stiffen.

‘Stand or I’ll blow your head off,’ the stranger ordered.

With the pistol already aimed at him, Captain Ross didn’t have a chance to take out his musket. He couldn’t do anything except get slowly out of the saddle.

‘Step away from the horse and turn out your pockets,’ the bushranger told the Captain. His eyes fixed on Jem over the top of the scarf. ‘Boy – don’t you move.’

Jem wasn’t going to. As long as the gun wasn’t pointed at him, he would be all right. He owned nothing worth stealing. He’d already lost the best thing in his life that day.

The Captain took a shilling and sixpence out of one trouser pocket, and a handkerchief out of the other. Then he held his hands in the air.

‘That’s lightweight for a gentleman like you,’ said the bushranger. ‘You’ve forgotten your coat pockets.’

Captain Ross lowered his hands reluctantly. His outside coat pockets did have more in them – coins, a ring of keys and a short knife.

‘Put them on the ground.’ The bushranger still held his gun level. ‘I’m waiting for your breast pocket. Either you empty it, or I’ll put a hole in it for you.’

The Captain gritted his teeth. He pulled a banknote from the inside of his coat. Jem watched it flutter onto the pile. He knew banknotes could be worth a lot, even more than thirty pounds. Seeing the money on the ground made his heart beat faster.

The bushranger wasn’t finished. ‘Why not take off your nice velvet coat?’ he said. His voice sounded to Jem as if he was smiling. ‘I could do with new trousers too.’

Captain Ross’s eyes bulged and his face went red. He undressed right there. Lucky for him, he was wearing long underwear. He looked a lot less like a Captain in tight grey smalls, Jem thought. More like a featherless emu.

‘Now leave the filly, and walk a hundred yards ahead,’ ordered the bushranger.

Captain Ross walked up the path, past the bushranger, with his hands held in the air. The bushranger’s gun followed the Captain the whole time.

When Captain Ross was far enough away, the bushranger stuffed his pistol into his belt. He walked down the path towards Jem and the horses. Jem’s palms were sweaty. He wondered if he should run. Jem was no slouch at running, but a shot would beat him. Like the one that got the Old Girl. He made himself stand still.

The bushranger didn’t seem too concerned about Jem. Instead he brushed dirt off the coat and put it on. He folded the silver coins inside the banknote. Then he rolled everything up in the Captain’s trousers and stuffed them in the Captain’s saddlebags. The man was so close Jem could see a small blue tattoo on the back of his hand.

The bushranger mounted Captain Ross’s horse. He tossed Daisy’s lead rein to Jem.

‘It’s been a pleasure doing business with you,’ he said. Jem could swear he was laughing under his scarf. The bushranger rode off, with the Captain’s cash and the Captain’s clothes.

Jem thought it served the iron-hearted Captain right. Secretly, he wished the bushranger had been rougher with Captain Ross. Jem could hardly believe the robbery had been so easy. As he watched the bushranger go, he admired his nerve, as well as the money in his bags.

2

After that, Captain Ross rode Daisy and made Jem walk to Ross Vale Station. All the way, Jem wished he could tell his dad what had happened. He wished he could be there to bury his dog. But he knew it could be a long time before he saw his dad again.

The Station sat in the middle of a flat paddock, not far from the creek. There were so many buildings it looked like a town to Jem. Lots of people were in the yard too: eight or nine stockmen were washing their hands, a woman in an apron passed a bucket to a boy, and a group of Aborigines stood by a side door.

They were almost all strangers to Jem. And they were all staring at him. Jem wanted to turn his back and walk right home. But his dad’s heavy boots had turned to stone, and he had blisters that hurt with every step.

Then Jem realised the people weren’t staring at him – they were staring at the Captain, stripped of his fine stuff. The Captain’s jaw had set like a rock. His face was so red you could light a match on it. Jem wanted to laugh.

‘Sir?’ A man stepped forward to hold Daisy’s reins. Jem recognised him as Mr Blain. He was the Captain’s overseer, second in charge, and too friendly. Jem’s dad said he was the sort of man who’d slap you on the back then dob you in to the master. Here Jem would have to work for him.

The Captain got off Daisy without a word. He pulled his riding gloves off, finger by finger, and tossed them at the overseer.

‘Get rid of the blacks from my house, Mr Blain,’ he said. He handed his whip to Mr Blain too.

The Captain went to his big front door. As it opened, Jem caught a glimpse of a long corridor with floorboards – not dirt – and painted walls. The windows had clear glass in them. It was a very fine house, like the Captain’s coat and horse and gun. Or at least, like the Captain’s coat, horse and gun had been, while they were still his, Jem thought. Captain Ross slammed the door behind him.

Mr Blain swung the Captain’s whip and cracked it over the heads of the Aborigines. Jem saw them flinch.

‘You no work,’ Mr Blain said, ‘we no give tobacco. No give flour.’

The black men shrugged their shoulders under their possum-skin cloaks and backed away.

Mr Blain shook the whip at them. Then he smiled at Jem. He had long yellow teeth like an old sheep’s.

‘Tell us what happened, sonny,’ he said.

‘We were crossing the creek, a few miles back,’ Jem mumbled. He wasn’t used to talking to strangers. ‘A man with a gun bailed us up.’

‘A bushranger!’ The other boy and the stockmen gathered around them. The boy was about the same age as Jem, but smaller. He had a whopper of a nose, though. ‘Is that how the Captain got his new suit of clothes?’ he said.

The stockmen laughed.

‘Alfie!’ The woman glared. The boy went quiet.

‘Which way did the villain go?’ the overseer wanted to know.

‘Back north,’ Jem said.

‘Towards Bungendore and the Sydney Road? Let’s hope he runs into the troopers,’ Mr Blain said. ‘If he’d gone for the hills we’d have to turn out after him.’

‘No more of this talk,’ the woman said. ‘Dinner is waiting.’

After dinner, Mr Blain led Jem across the dark yard. He pointed out his own hut, next to the cottage of Mrs Goods – the cook – and her boy Alfie. He led Jem to the farm hands’ lean-to, up against the brick stables.

Mr Blain held an old blanket out to him. ‘I bet the Captain rues the day he brought you in,’ he said. He winked as if it was a joke. ‘Not a good start to your employment, hey?’

Jem didn’t find that funny. It had been a hell of a start, and it was the Captain’s fault.

Jem took an empty bunk. He wrapped the blanket tight around him, but his feet were cold as a lazy man’s dinner. The Captain’s horses had better sleeping quarters than his men. Jem’s thoughts were even colder than his feet. He missed home. He hated the Captain for putting up the price of the land. He wasn’t happy his dad had let the Captain take him away. And he didn’t like remembering his dad standing there, uselessly twisting his hat, while their dog . . . Jem tr

ied not to think about her anymore.

Jem did not want to be like his dad. Being miserable and beaten was hard to take. Being angry was better. Jem thought the bushranger had taught him something. He had shown Jem that you didn’t have to let the Captain get his way. If you dared.

Jem stared into the darkness. He heard the soft stamping and huffing of horses from inside the stable, through a hole where a brick was missing.

There was another sound too, higher. What was it? A whimper?

The other men had gone to sleep. There was the noise again – it sounded almost like a little kid. Jem didn’t stop to think whether it was his business. He got up. With the blanket wrapped around him he crept to the stables.

A shaft of grey moonlight slanted through the hole. The corners of the stable were pits of darkness. The sound came again, from one of the corners. Yip, yip, aa-oo.

Jem felt his way forward. The pile of straw was warm under his feet. A creature had been lying here.

Ow. He stubbed his toe on a wooden barrel. Then he felt a damp nose sniffing around his ankle. It was a dog. Jem stood still. He was new to the Station so he’d better let the dog get to know him. He held out a fist for it to sniff.

Yip, yip. The whimpering noise started again, and it wasn’t the dog at his feet. Jem thought it was in front of him, inside the barrel. He couldn’t see. He felt for the edge and leaned over, reaching inside. His fingers went down through air until they brushed something warm. Then a hot tongue rasped his hand – a puppy.

‘How did you get in here, silly critter? Quit licking a minute, will you?’ Jem put both hands in the barrel. His fingers went under the puppy’s belly where the skin was bare and soft. ‘Don’t wriggle!’ The puppy squirmed madly, wagging its whole behind. Puppies rated higher than people and even higher than money to Jem. Unlike money they grew by themselves, and unlike most people they loved you back.

‘There you go.’ He put it down beside its mother. The mother’s tail banged happily on his legs. She turned a few circles in the straw, and settled down. The puppy scrambled over Jem’s feet. Jem heard it scuffling in the straw. Then it scrambled back over his feet again and pulled at his trouser leg with its teeth.

Do You Dare? Bushranger's Boys

Do You Dare? Bushranger's Boys